"Our fate restricts us so that our destiny can find us...." — Michael Meade

Our fate restricts us so that our destiny can find us, so that we can find again the gifts we came to give the world and receive the blessing the world would give to us.

— Michael Meade, Fate and Destiny

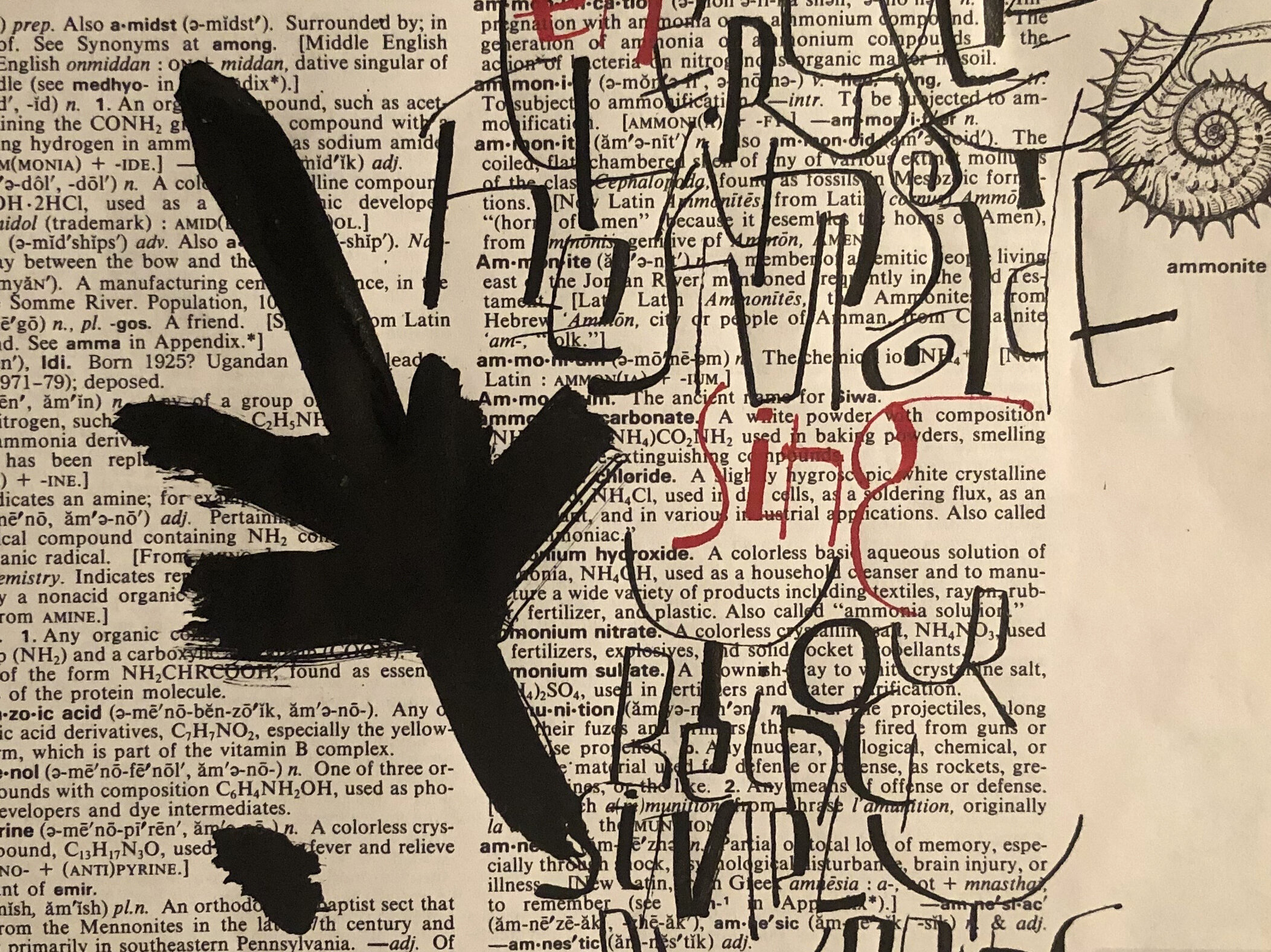

When something happens that common notions don’t have enough gravitas for understanding, the old stories talk about the “hand of fate”. The Greeks have many stories about prophecies, fate and destiny — and the danger of dismissing the signs.

Now the whole world is tied together by this “hand of fate”. It is as if the planet really is alive with intelligence, insisting that we slow down. Alongside the tragedy of illness and death all around, there is the sense of destiny, of something larger than all of us, forcing us to go inward, or live in trauma.

I have thought a long time about the words, fate and destiny. I am not a Calvinist, I don’t think everything is pre-determined. I believe that every choice matters. And yet, there is this ancient notion of fate as an invisible thread that is woven through all the things of the world and all the events in time. (Michael Meade). It includes an awareness of the limitations we have been given, including death. Fate is the hand you are dealt. Destiny is how you play your hand, how you choose to live into your fate, and find meaning in what you have been given. Your destiny is fully realized because of your limitation. There is an inherent connection between your inner gift and your inner wound. The door is through willingness to be vulnerable, to accept your limitation as a structure that supports your soul’s expression.

"All shall be well." — Julian of Norwich

When Julian of Norwich was about 30 years old, she was struck with an illness so severe she knew she would not survive. When she was administered last rites, she began to experience visions from God. Fifteen visions lasted throughout the afternoon of 13 May 1373 CE. A final vision came the next evening, when she woke completely cured and, shortly afterwards, wrote them down. She is the author of the phrase made famous by T S Eliot: “And all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

This declaration that “all manner of thing shall be well” does not eliminate misfortune, sickness or death. It is pointing to what all the respected wise ones say about the ability to find peace, and even joy, in the eye of the storm — to come to trust that there is something that transcends chaos and impermanence.

Practicing accepting whatever comes is often misunderstood to mean being passive, or not taking action. This is incorrect. Acceptance is the knowledge that opening to what is creates the ability to act more effectively, with clarity. Saying “yes” to whatever storm hits is an ongoing practice. It comes from knowing that anxiety is contagious, pervasive and debilitating. It easily folds itself into anyone else’s anxiety, and multiplies. It can even become a convenient entertainment, keeping you stuck in a story that limits your ability to see or act in a meaningful way. Welcoming what comes resides in vanquishing any thought that your situation should be any different than it is. I can already feel the freedom in this.

The Revolutionary Act of "Doing Worthy"

Doesn’t everyone have a day when things fall apart? When it takes more effort than you think you have to put one foot in front of another? When even your technical devices seem to collude against you?

My reverie, pure joy, after my exhibit was done, ended abruptly with a letter from the IRS announcing they are coming to audit my business next week. On top of this, my intrepid father, at 96, fell for the first time and broke a bone.

So my retreat here at St Meinrad, scheduled so long ago, has been infiltrated with dread and piles of papers. The amount of sorting and retrieving of records is overwhelming, seven detailed pages of requests from the IRS … which calls to mind, once again, the old Greek story of Psyche. Her first impossible task was to sort seven different kinds of seeds, filling a gigantic room, floor to ceiling, before nightfall, before Aphrodite announces her time is up. I am thankful for these stories, and for the way a story puts the human dilemma in perspective. Just this morning, on my first day of this retreat, my son, who was born a muse, called. Ma, I had this dream. In a big room were all these small piles of seeds neatly sorted, and a spiral of seeds floating upward.

There are a few spaces in my classes at ABC 2020 in Alberta, Canada this summer:

Image Making: Then & Now | Exhibit Opens Nov 15: Laurie Doctor & Martin Erspamer, OSB

This week I have been reading Image Making in Arctic Art*, an article written in the 1960s about the the indigenous people living in the desolate Arctic tundra. It’s hard for most of us to imagine that in addition to no electricity, running water, heat, etc. …it is so cold that nothing grows. No trees in a flat landscape. They live in a white and gray shifting world of wind and ice. Life is uncomplicated by email, texts, phones, radio, TV, internet, cars, and airplanes. Their days are made of bare essentials — of finding food and oil for their lamps, to have enough light and warmth inside their ice igloos. In this bare existence, poetry and art are also part of survival. Poetry and art are food. There is no separation made between the need for the hunt and the need to create. Being makers is part of their sustenance. They make their own music, singing and humming as they work, reciting poetry, asking the unformed tusk: Who are you? Who hides there?

Edmund Carpenter* records a story from the 1700s of two Arctic hunters following a snowshoe print in the vast empty landscape; it leads to a young woman sitting alone in a hut. She has been there for seven months without seeing a single human. She tells of her whole family — her parents, her husband and her baby — being murdered by a hostile band. She alone survived. What struck these hunters most deeply was her dignity and composure. In spite of this unimaginable loss, and having to survive alone for months by snaring small game, she sat beautifully dressed, taking the time in her isolation and grief to decorate her dress with small found objects, placed in pleasing patterns.

Perhaps in the story of the young woman there is also the idea that you can open your imagination to finding what you need to be a maker, regardless of the circumstances you find yourself in.

Images from student work at Ghost Ranch

I am devoting this post to showing the work done by students in our recent class at Ghost Ranch. Please forgive this long absence — all my attention has been given to my class, and to finishing my paintings for my upcoming exhibit. Another post will be coming soon with some images from my show.

It is impossible, after a rich experience, to convey it all in words or images. This will give you a glimpse of the place, which has its own power and presence, and some of the work that was done.

It is not my job to praise or blame, only, in the end, to be envious of your work.

— William Stafford to his students

In the atmosphere of New Mexico high desert, we combined working with the Tarot cards (to strengthen intuition and inner imagery), with writing, painting and bookmaking…

Presence and Productivity

What I want to talk about today is how to find a balance between solitude and interaction, and how bringing presence to both cultivates productivity. Being a maker requires both solitude and interaction. Quality solitude awakens your inner life, your muse and your imagination. Meaningful interaction — a conversation with a fellow traveler — fuels creativity. Joseph Campbell said: “We may as well be with those who bring out the best in us.” How you spend your days, and who you spend them with, matters.

A full day of solitude is water for the thirsty maker…on these days, I often take a long time getting out of my pajamas. Breakfast is late too, but before noon. The length of time for dedicated solitude is less important than the quality of solitude. Quality is the renewal, the welcoming of a fresh horizon, that arises naturally from stillness. Yet stillness seems so distant to the restless mind. It’s as if everything is aligned in opposition to having an inner life. There is an aversion to boredom, a craving for stimulation, and a longing for the next shiny object. Let me give you an example:

There was a research study set up to examine our resistance to “doing nothing”. The participants were asked to sit alone in a room, without moving or having access to any devices, for 10 minutes. They were given the option to sit still, or to press a button that would give them an unpleasant electric shock. 25% of the women and 67% of the men chose to shock themselves rather than sit still.

It’s as if we don’t want to allow the presences tapping on our dark and luminous world of possibility, the images that are summoning us, to actually arrive and expand our being.

Uprooter of Great Trees

I want to tell you a story — a very old story — that I heard from Laurens van der Post.* It speaks to the necessity of embracing paradox, and off the suffering caused by dualistic thinking: when things are either this or that; when you are either going to succeed or fail; when anything or anyone is either good or bad; when something is either right or wrong. Dualistic thinking renders us unable to deal with the difficulties and paradoxes that life inevitably brings. Spending most of my daylight hours painting, I notice that I need to hold the paradox of having structure alongside the need to be self-forgetting — the fool who jumps in.

I shared this story in a recent class in New Mexico. One of the students arrived at the last minute because of a family emergency. For the entire week she chose to remain silent in her grief, only saying: I cannot speak about it. And so she worked, allowing her hands to give shape to her grief.

Once upon a time, in a faraway place…..

The Presence of a Tree

Twice a year I return to Taos, New Mexico to teach. Outside our lodge at the Mabel Dodge Luhan Retreat there is a magnificent old cottonwood tree. It is fed by water in the arroyo it rises above.

At our refuge in Taos, situated next to sacred Pueblo land, we feel the closeness of the landscape. It is high desert, and the presence of this tree is welcome shade and vertical majesty.

"Now we will count to twelve and we will all keep still." – Pablo Neruda

This week I went to my local bookstore, and asked the clerk: Why is it that if I buy a new notebook, I think I may write something worthwhile? Nonetheless, inspired by spring, I bought a new little notebook for my new lists, along with Austin Kleon’s Keep Going, which I have really enjoyed reading this week.